If you are teaching children, or are the parents of children who are learning about the Stone Age to Iron Age topic in primary schools in England, you might want to find a museum to visit to see some objects from these exciting periods on display. We’ll update this blog post as we find or hear about museums with great prehistoric collections, so if you find one, let us know in the comments below. You may also be interested in places where you can visit replica Stone Age to Iron Age houses, or in museums with school workshops on offer. In this post we’re starting from the south and heading northwards by region.

London

The British Museum has two galleries (numbers 50 and 51 on the upper floor) dedicated to Britain and the Near-East from 10,000 BC to 800 BC (Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age) and Britain from 800 BC to AD 43 (Iron Age). The earlier gallery focuses on the invention and adoption of agriculture. The later gallery contains objects such as the Mold Gold Cape from Wales, Snettisham torc hoard, and the remains of Lindow Man.

The Museum of London has a gallery called London before London, with a focus on objects from the Thames itself. Highlights include the reconstructed face of a Neolithic woman from Shepperton, a resin copy of the Dagenham Idol (the original is in the Valence House museum in Dagenham itself) and a partial reconstruction of the interior of an Iron Age roundhouse.

The Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy in London might appear not to be a place to go to find out about human prehistory, but they do have a few animal skeletons on display that early humans would have come across when they first arrived in Europe, like giant deer skulls, as well as the skeletons of early humans (hominins) like Homo erectus.

Similarly London’s Natural History Museum also has displays on human evolution as well as those animals that lived in Britain and Europe both in the warm and cold periods of the Ice Ages at the time of hominin and modern human inhabitation.

South-east

Reconstruction of the interior of a Bronze Age roundhouse

Dover Museum houses the Dover Bronze Age boat, which is an incredible and near unique survival from this time. It does also have a partial reconstruction of the interior of a Bronze Age roundhouse complete with mannequins in replica costumes based on finds from Denmark.

Tunbridge Wells Museum in Kent has Stone Age to Iron Age artefacts from the High Weald on display in Room 2 of the museum.

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has a gallery of prehistoric artefacts, including an intriguing pair of spoons, one with a hole and one engraved with a cross. They have been interpreted as a fortune-teller’s kit. Other highlights include carved stone balls from Scotland, Bronze Age gold earrings, an Iron Age coin hoard, and Bronze Age and Iron Age swords and shields.

Some casts of famous Palaeolithic portable art in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Also in Oxford are the Museum of Natural History and the Pitt Rivers Museum (they are attached to each other). The Museum of Natural History has a display on the evolution of humans, as well as a cast of the Red Lady of Paviland (actually the skeleton of a man dated to around 30,000 years ago found in Wales) and a display on how stone tools developed over time, as well as some casts of beautiful Ice Age portable art. Be aware you will have to deal with questions about the Venus of Willendorf’s body!

Flint arrowheads on the top floor of the Pitt Rivers Museum – not necessarily all from Britain

The Pitt Rivers Museum has stone, bronze and iron tools and weapons on the top floor and will eventually also have more archaeology displayed there exploring the quest for food from the Stone Age to the Iron Age.

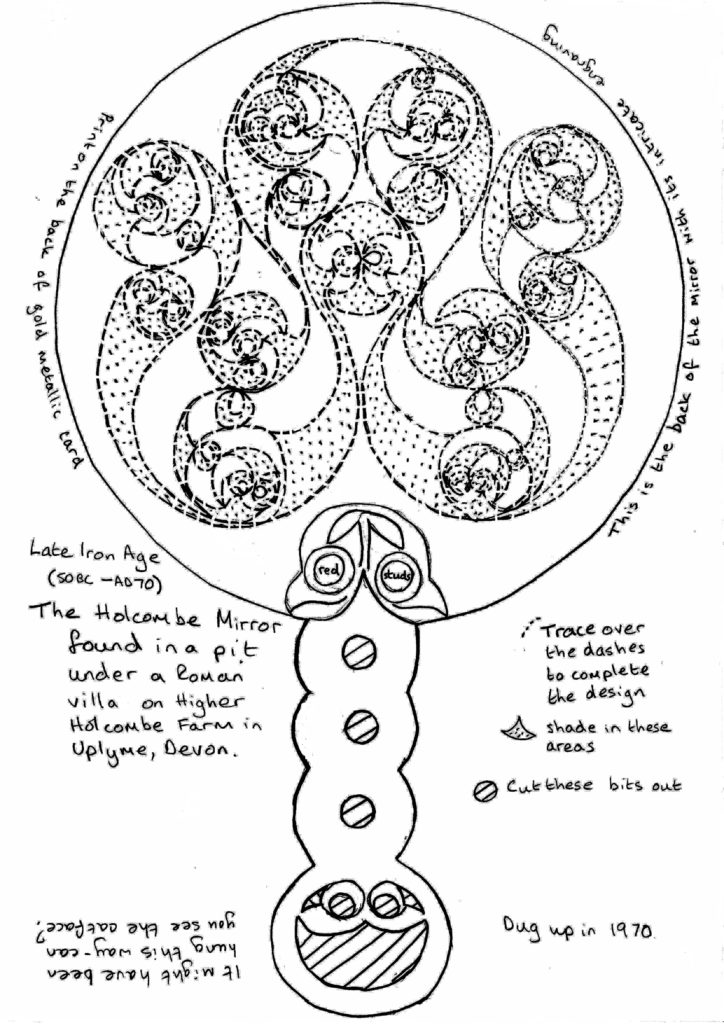

Buckinghamshire County Museum in Aylesbury has a gallery on the prehistoric and Roman history of the county, including drawers full of Ice Age fossils, like mammoth teeth, and then much later objects such as the Late Iron Age mirror from Dorton and an Iron Age coin hoard.

The Higgins Bedford’s collections on display in the Settlement gallery include stone tools discovered by the Victorian collector James Wyatt (1818-1878) in local gravel pits. Two flint hand axes found next to a piece of fossilised mammoth leg bone showed that early humans lived alongside long-extinct animals, showing that humankind was far more ancient than most people at the time believed. A reconstruction of the recently-excavated 3,800 year old burial of a Bronze Age archer from Great Denham shows a high-status young man in his twenties, as revealed by the beaker pottery, bronze dagger and finely crafted stone wrist-guard with which he was buried.

Luton’s Stockwood Discovery Centre has a great gallery showing finds from around Luton, some of which come from Waulud’s Bank in North Luton, an unusual ‘D’ shaped Neolithic enclosure at the source of the River Lea.

Haslemere Museum in Surrey has a collection of flint tools on display from Blackdown, West Sussex.

Guildford Museum has a permanent exhibition of some of the prehistoric artefacts found locally, including bronze spear-heads.

On the south coast is Bexhill Museum in East Sussex which has some local prehistoric artefacts in the Sargent Gallery.

Although The Novium in Chichester was built to house the Roman bath-house and displays mainly Roman collections, it also currently has Bronze Age Racton Man, killed in two fatal blows and buried with his bronze dagger, in a temporary exhibition.

The Redoubt Fortress and Military Museum in Eastbourne has a year-long exhibition on called Treasure which includes some Stone Age artefacts.

South-west

The Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro has an impressive collection of prehistoric artefacts, especially Bronze Age objects including three gold lunulae which are the subject of a beautiful poem by Penelope Shuttle. They also have Iron Age objects including a slate knife from Harlyn Bay and a decorated mirror.

The Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter has an important collection of prehistoric archaeology from Devon, including 350,000 stone tools from gravel pits near Axminster and finds from Neolithic and Bronze Age burials. It is also the current home of the Kingsteignton Idol.

Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery has a gallery called Uncovered which spans from the Bronze Age to the medieval period and has examples of Bronze Age tools and weapons among other things. With any luck some of the objects from the amazing Whitehorse Hill cist burial that were temporarily on display there in 2014 will come back to the museum permanently. If you look carefully, you’ll also be able to see some remains of Ice Age animals in the Explore Nature gallery.

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery has a temporary exhibition on until June 2017 on Stone Age to Iron Age Bristol including Bronze Age swords and Iron Age jewellery.

Gloucester City Museum has prehistoric objects on display.

Salisbury Museum is an essential accompaniment to a visit to Stonehenge itself (which also has a fantastic museum). The Stonehenge Archer and the Amesbury Archer are both here, the former was a man buried in the ditch of Stonehenge with arrowheads that would have been embedded in his flesh and bones. The Amesbury Archer had come from the Alps and brought with him the earliest dated metal objects in the country.

Wiltshire Museum in Devizes has a great deal of the artefacts from barrows around Stonehenge in its Gold at the Time of Stonehenge gallery, including collections from the Bush Barrow, the Golden Barrow and a possible shaman’s burial. These are important evidence of the role of Stonehenge as a religious monument and focus of high status burials in the early Bronze Age.

The Alexander Keiller Museum is within the henge of Avebury itself and houses the collection of Alexander Keiller who dug at Avebury and nearby Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure (Neolithic meeting places). The remains of burials from the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age are on display here.

Dorset County Museum in Dorchester houses many of the objects found in excavations at the nearby Iron Age hillfort Maiden Castle and currently has an appeal to raise enough money to buy a lovely late Iron Age mirror found in a burial in the Chesil area.

Remains of hunter-gathering and farming communities have been found on land and under water in the Solent and some are housed at Southampton Seacity Museum.

Poole Museum houses the very handsome remains of the Poole Logboat, which is 2300 years old. At 10m long, it is the longest logboat ever found in southern Britain and was found in Poole harbour during dredging.

City Museum in Winchester has displays about the history of the area from the Iron Age.

Andover Museum of the Iron Age is a small community museum, but the Iron Age section has a wonderful collection of artefacts and reconstructions/dioramas, with lots of information on Danebury Hillfort. There is also information on the occupation of the Test Valley from Neolithic to modern times.

East Anglia

Including Cambridgeshire in East Anglia, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of Cambridge University (MAA) has some great collections of prehistoric artefacts, including tools made by early humans from Olduvai Gorge in east Africa, collections from the Mesolithic site at Star Carr in Yorkshire and an Iron Age mirror from Great Chesterford in Essex.

Flag Fen near Peterborough not only has reconstructed Bronze Age houses but also a museum containing some of the huge number of bronze weapons thrown into the fen from the wooden platform that was revealed in a groundbreaking excavation in the 1980s. Recent excavations nearby at Must Farm uncovered the remains of eight logboats, which are also being conserved at Flag Fen and are regularly on display there.

Peterborough Museum has an archaeology gallery including a prehistoric murder victim and one of the finest Iron Age swords ever found.

Chatteris Museum is nearby to Peterborough and currently has an exhibition of the Ancient Human Occupation of Chatteris including 500,000 year old flint axes and many replica objects that can be handled, including a Bronze Age sword and shield.

Wisbech and Fenland Museum has an archaeology collection including an Iron Age decorated scabbard dating to about 300 BC among many other locally found objects.

Ancient House Museum in Thetford, well-known as a Tudor manor house, also has some objects from nearby Grimes Graves (a Neolithic flint mine that can also be visited) including a polished stone axe and bat bones.

Lynn Museum in King’s Lynn has the wonderful Seahenge on display. You can appreciate the size of this timber circle that was found on the coast of north Norfolk with an upturned oak tree in the centre. Other exhibits include a hoard of Iron Age coins hidden in a cow bone at Sedgeford in Norfolk, a find our director Kim Biddulph saw first hand as it came out of the ground!

Photo courtesy of Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse

Gressenhall Museum near Dereham in Norfolk has a display on the first farmers in the Neolithic. Norwich Castle, in contrast, has a gallery on the Iron Age. Both of these are part of Norfolk Museums.

Colchester Castle in Essex has a great collection of objects relating to the Iron Age oppidum (a type of early town) of Camulodunon, a fore-runner of Roman Camulodunum. Finds from the Lexden burial include a medallion depicting the Emperor Augustus and were given as a gift to a client king in Essex, possibly Cunobelin, whose coins can also be found in the museum. There are earlier objects too, including a beautiful bronze cauldron from Sheepen that attests to a late Bronze Age feasting culture.

Ipswich Museum houses some Iron Age collections as well as a gallery of the wildlife of Britain from 10,000 BC to today – which animals would our prehistoric ancestors have known? Which animals that we are familiar with today are invasive?

Mildenhall Museum near Thetford hosts some impressive Roman and Anglo-Saxon finds, but it also has a gallery of prehistoric artefacts.

East Midlands

Creswell Crags is on the Nottinghamshire/Derbyshire border and is a gorge in which many caves were inhabited, first by Neanderthals about 50,000 years ago and then by modern humans about 10,000 years ago. The only figurative piece of Ice Age portable art in Britain has been found here, and engraved drawings can also be seen inside the caves.

Buxton Museum in Derbyshire is currently closed fgor refurbishment, but has teeth and bones of Ice Age animals from various caves in the county, as well as some human-made artefacts from prehistory.

Jewry Wall in Leicester has extensive archaeology collections including stone tools.

Prehistoric pottery vessels in Charnwood Museum. Photograph courtesy of Leicestershire County Council.

Charnwood Museum in Loughborough includes local objects dating from the Neolithic to the Iron Age such as tools, jewellery, pottery vessels and a chariot fitting. A rare Bronze Age axe mould is a recent addition to the displays. Objects buried with the 4000 year old Cossington Boy are included alongside a reconstruction of his burial.

Bronze Age objects on display in Melton Carnegie Museum. Photograph courtesy of Leicestershire County Council.

Melton Carnegie Museum in Melton Mowbray includes prehistoric objects from the local area including flint and stone tools and beautiful Bronze Age pygmy cup which may have been used in rituals. Also features the nationally important Bronze Age Welby Hoard of bronze axes, sword, spear, harness fittings a bowl. The hoard gave its name to a type of axe. Iron Age finds include a gold coin of the local Corieltavi tribe and pottery from the nearby hillfort at Burrough Hill.

Part of the Iron Age Hallaton Treasure to be seen at Harborough Museum. Photograph courtesy of Leicestershire County Council.

Harborough Museum and Market Harborough Library, Market Harborough includes the fantastic Hallaton Treasure (www.leics.gov.uk/treasure) a collection of Late Iron Age and Roman objects buried at a shrine of the local tribe, the Corieltavi, between 50 BC and just after the Roman invasion of AD 43. See 2500 Iron Age and Roman gold and silver coins, jewellery, a unique silver bowl, ingots, pig bones and a beautiful and rare silver gilt Roman cavalry helmet which make up this amazing discovery. Also, see some of the earliest pieces of metalwork from Britain – the Gilmorton Basket Ornaments – a pair of gold earrings or hair ornaments from the Copper Age c.2500 BC. Other prehistoric objects include a rare cannal coal button dating to the Bronze Age and prehistoric pottery.

The Collection in Lincoln has archaeology galleries that cover Stone Age tools, Bronze Age burials and early metals, and Iron Age swords and shield given to the spirits of the River Witham. The Iron Age Fiskerton log boat is also on display there.

The Norris Museum in Huntingdon is a small museum with some lovely prehistoric collections, including Iron Age cart fittings from Arras culture burials.

West Midlands

The Herbert Museum and Art Gallery in Coventry has prehistoric objects on display, including some Iron Age metal-working crucibles from the Post Office sorting depot site.

The Market Hall Museum in Warwick has refurbished displays including some prehistory, especially the giant deer.

The Potteries Museum in Stoke-on-Trent has prehistoric artefacts on display in the archaeology gallery, including prehistoric pottery and early examples of tools and metal-working.

North-east

Yorkshire Museum in York has prehistoric objects on display from flint tools to some of the chariot burials from the Arras culture in the East Riding of Yorkshire. There is also a special exhibition on until 2016 of the Mesolithic objects from Star Carr in After the Ice. In the next two years they will run exhibitions on Bronze Age and Iron Age Yorkshire.

Neolithic jadeite axehead. Image copyright Leeds Museums and Galleries. Photograph by Norman Taylor.

Bronze Age necklace made of Whitby jet. Image copyright Leeds Museums and Galleries.

Bronze Age axe head and mould. Image copyright Leeds Museums and Galleries.

A musical pipe made from a sheep’s leg bone. It was found when an Iron Age burial site at Malham Moor was excavated. Image copyright Leeds Museums and Galleries. Photograph by Norman Taylor.

Leeds Museum has displays of Mesolithic and Neolithic flint and stone tools, a Bronze Age jet bead necklace (made from Whitby jet) and both bronze moulds and casts. They also have a partially reconstructed Iron Age roundhouse and artefacts from the Iron Age settlement at Dalton Parlours. These are all in the Leeds Story gallery.

Neolithic carved stone found on Fylingdales Moor. Photo by Graham Lee, North York Moors National Park Authority.

Whitby Museum itself has a collection from the nearby Mesolithic site of Star Carr, Neolithic flint tools, Bronze Age bronze weapons and tools and a copy of one of the Neolithic carved stones from Fylingdales Moor.

Weston Park Museum in Sheffield currently has an exhibition until 20th September 2015 on Life on the Edge, all about life at Creswell Crags in various Ice Ages. Prehistoric objects excavated from South Yorkshire and the Peak District are on display here including flint implements from Mesolithic sites such as Deepcar and grinding stones used for flour production in Iron Age Wharncliffe.

Tolson Museum in Huddersfield has prehistoric objects on display.

Copies of the Iron Age Roos Carr figures at Dover Museum. The originals are in Hull and East Riding Museum.

At Hull & East Riding Museum you can walk through a reconstructed Iron Age village complete with chariot and see the enigmatic Roos Carr figures. There is also the Iron Age Hasholme logboat to see on display.

Scarborough Rotunda displays some archaeological artefacts, as well as Gristhorpe Man, a skeleton buried in a hollowed out tree trunk in the Bronze Age – something qoite common in Denmark but not so much in Britain.

Objects in Ryedale Folk Museum. Photo courtesy of Spencer Carter.

Ryedale Folk Museum in Hutton-le-Hole, North Yorkshire, has displays of flint tools and objects from a waterlogged Iron Age sites along with its reconstructed Iron Age roundhouse.

Swaledale Museum in North Yorkshire also has local prehistoric objects.

The Dales Countryside Museum in North Yorkshire has some local prehistoric objects including flint tools from Wensleydale that date back to the end of the last Ice Age around 13,000 years ago.

The Great North Museum: Hancock houses the prehistoric collections from Wearside, including a logboat, cup and ring marked stones, 174 Neolithic stone axes, Bronze Age burials, hoards, tools and weapons.

Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens also has prehistoric objects on display.

The Gainford Stone, a slab of rock carved with prehistoric cup and rings patterns, is only one of a number of local prehistoric artefacts to be found in the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle.

Durham University’s Museum of Archaeology houses locally found prehistoric including cup and ring marked stones, microliths made by hunter-gatherers around 7000 BC as well as artefacts from the farming era including jet jewellery, cremation urns from Crawley Edge, Stanhope and a bronze sword from Houghall.

Palace Green Library in Durham will have a new exhibition devoted to the last 10,000 years of Durham from 26th July called Living on the Hills in the Wolfson Gallery.

North-west

Manchester Museum, part of the university, has objects from Alderley Edge in Cheshire, where there was, among other things, a copper mine in the Bronze Age. Some Palaeolithic objects from Creswell Crags in Nottinghamshire are also on show here. There are also bronze hoards from the River Ribble and gold bracelets from Malpas.

The Museum of Liverpool has a gallery called History Detectives which includes some prehistoric objects, including a burial urn from Wavertree that would have contained the burnt bones of someone from the Bronze Age.

Clitheroe Castle Museum has displays about the area’s prehistory as well as history, including burial urns from Pinder Hill.

The Harris Museum in Preston has ancient human and animal bones from the Preston Dock excavations that date back 6000 years, Bronze Age burial urns from the Bleasdale timber Circle and a giant elk from the end of the last Ice Age.

Saddleworth Museum in Oldham has local prehistoric objects on display.

Tullie House in Carlisle has important objects from the Langdale axe factory from which many ground stone axes were distributed across the UK and abroad in the Neolithic period. A Bronze Age display is housed in a replica wooden roundhouse in the Border Galleries.

Forget the name of this page – Outdoor Archaeological Learning – and think of it as indoor archaeological learning. There are three booklets on this page. The first is aimed at teachers and educators but there are some cut out and make models of archaeological sites and a timeline activity you could do with cut-out Lego figures through the ages.

Forget the name of this page – Outdoor Archaeological Learning – and think of it as indoor archaeological learning. There are three booklets on this page. The first is aimed at teachers and educators but there are some cut out and make models of archaeological sites and a timeline activity you could do with cut-out Lego figures through the ages. Into the Wildwoods and The First Foresters are focused on the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods of Scotland and have characters created by Alex Leonard who could be the basis of story-telling. There are also map-making and drawing activities and lots of illustrations and photographs inside.

Into the Wildwoods and The First Foresters are focused on the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods of Scotland and have characters created by Alex Leonard who could be the basis of story-telling. There are also map-making and drawing activities and lots of illustrations and photographs inside. Teaching History in 100 Objects was a British Museum project to support the new history curriculum in English schools from Key Stages 1-3 so the topics are linked to that. This is aimed at teachers but there are lots of objects to look through (not just 100 – each focus object links to many more). See if there’s an object that links to a topic your child/ren have been studying/are interested in. There are objects from Palaeolithic handaxes to a badge from Jesse James’ bid for the Democratic nominee in the presidential elections of 1984.

Teaching History in 100 Objects was a British Museum project to support the new history curriculum in English schools from Key Stages 1-3 so the topics are linked to that. This is aimed at teachers but there are lots of objects to look through (not just 100 – each focus object links to many more). See if there’s an object that links to a topic your child/ren have been studying/are interested in. There are objects from Palaeolithic handaxes to a badge from Jesse James’ bid for the Democratic nominee in the presidential elections of 1984. The Young Archaeologist’s Club website has loads of activities to do on its website, including making Viking flatbread, doing your own cave art, making archaeological fake poo for your kids to excavate and so much more.

The Young Archaeologist’s Club website has loads of activities to do on its website, including making Viking flatbread, doing your own cave art, making archaeological fake poo for your kids to excavate and so much more. I absolutely love the comics of Dr Hannah Sackett on Prehistories. They are beautifully illustrated and wittily written. They are free to read online or download and print.

I absolutely love the comics of Dr Hannah Sackett on Prehistories. They are beautifully illustrated and wittily written. They are free to read online or download and print. Paper models of Neolithic houses have been created by Jools Wilson of Bears Get Crafty to download for free.

Paper models of Neolithic houses have been created by Jools Wilson of Bears Get Crafty to download for free. English Heritage has paper Bronze Age roundhouse models to download and make.

English Heritage has paper Bronze Age roundhouse models to download and make.

Viper’s Daughter is the next in the Chronicles of Ancient Darkness series by Michelle Paver which started with Wolf Brother. It is published by Zephyr, an imprint of Head of Zeus books on 2nd April 2020. We have

Viper’s Daughter is the next in the Chronicles of Ancient Darkness series by Michelle Paver which started with Wolf Brother. It is published by Zephyr, an imprint of Head of Zeus books on 2nd April 2020. We have

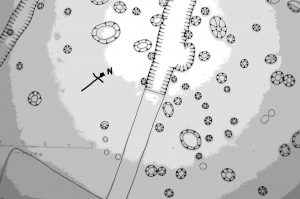

Based on this site, I developed a game similar to Cluedo for Aylesbury Young Archaeologist’s Club where players would try to work out who had started the fire, how and in which building. I colour-coded a reconstruction drawing by

Based on this site, I developed a game similar to Cluedo for Aylesbury Young Archaeologist’s Club where players would try to work out who had started the fire, how and in which building. I colour-coded a reconstruction drawing by

![Gundestrup Cauldron. By Rosemania (http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/4121249312) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/800px-Silver_cauldron-300x196.jpg)

![Basse-Yutz flagons. By British_Museum_Basse_Yutz_flagons.jpg: [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/British_Museum_Basse_Yutz_flagons_1-300x185.jpg)

![St Chad's Gospel. By The original uploader was Claveyrolas Michel at French Wikipedia (Transferred from fr.wikipedia to Commons.) [CC SA 1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/sa/1.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Lichfield_monog_Christ-227x300.jpg)

![18th century engraving of a Wicker Man. By UnknownMidnightblueowl at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/WickerManIllustration-214x300.jpg)

![Edinburgh Beltane Festival 2012. By Stefan Schäfer, Lich (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/640px-Edinburgh_Beltane_Fire_Festival_2012_-_Bonfire-300x200.jpg)